First consultation?

Need a refill?

First consultation?

Need a refill?

The Importance of Sleep: Enhancing Health, Mind, and Performance

Lifestyle

Eileen Quinones

•

15 mins read

• Oct 15, 2024

Sleep is a cornerstone of human health, as essential as exercise and nutrition. It supports physical recovery, cognitive function, and emotional well-being. Despite this, many people underestimate its importance, leading to widespread sleep disruption that negatively impacts performance and health. This blog dives deep into the science of sleep, the health risks associated with poor sleep, and practical strategies to cultivate healthy sleep habits.

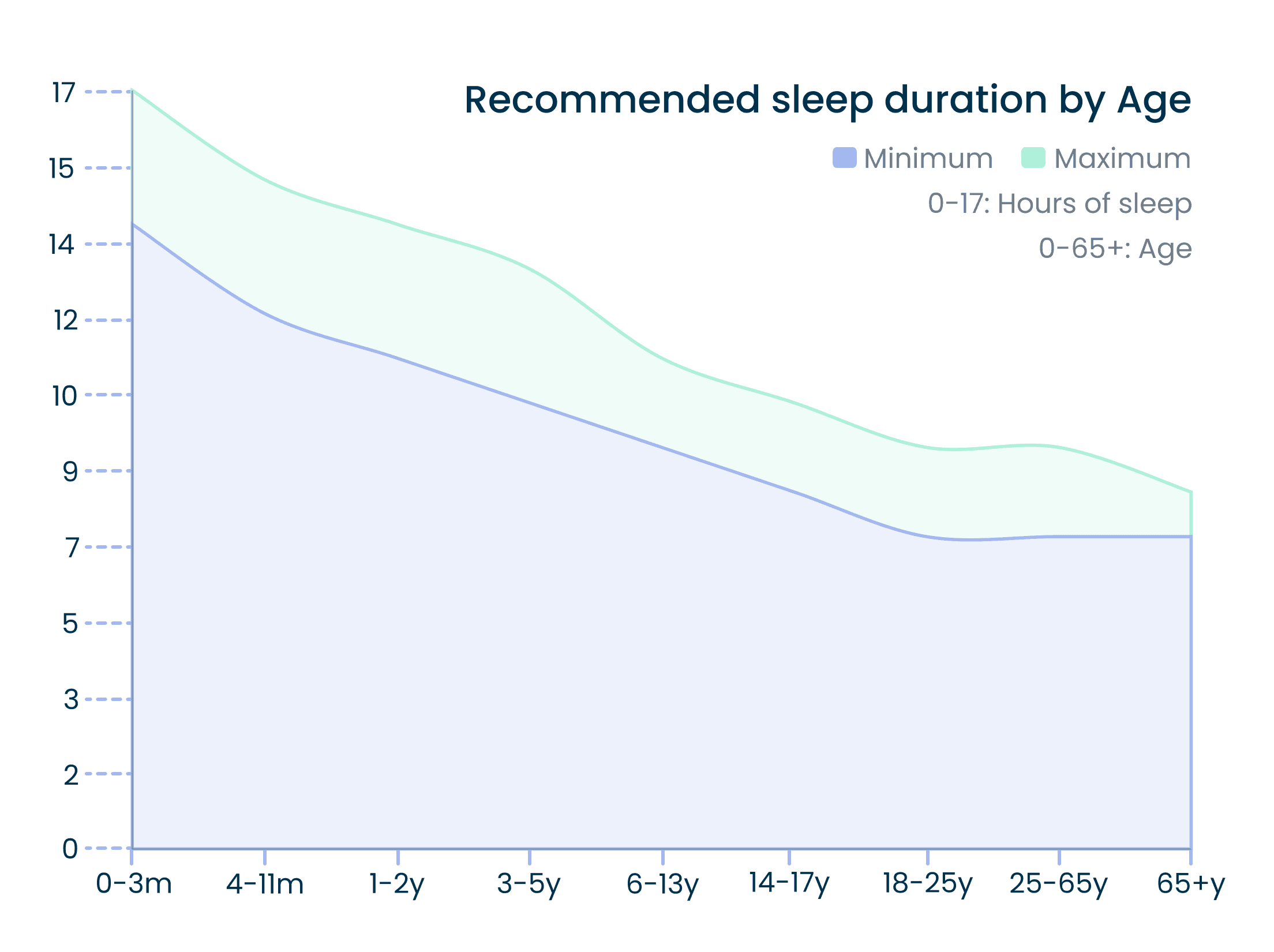

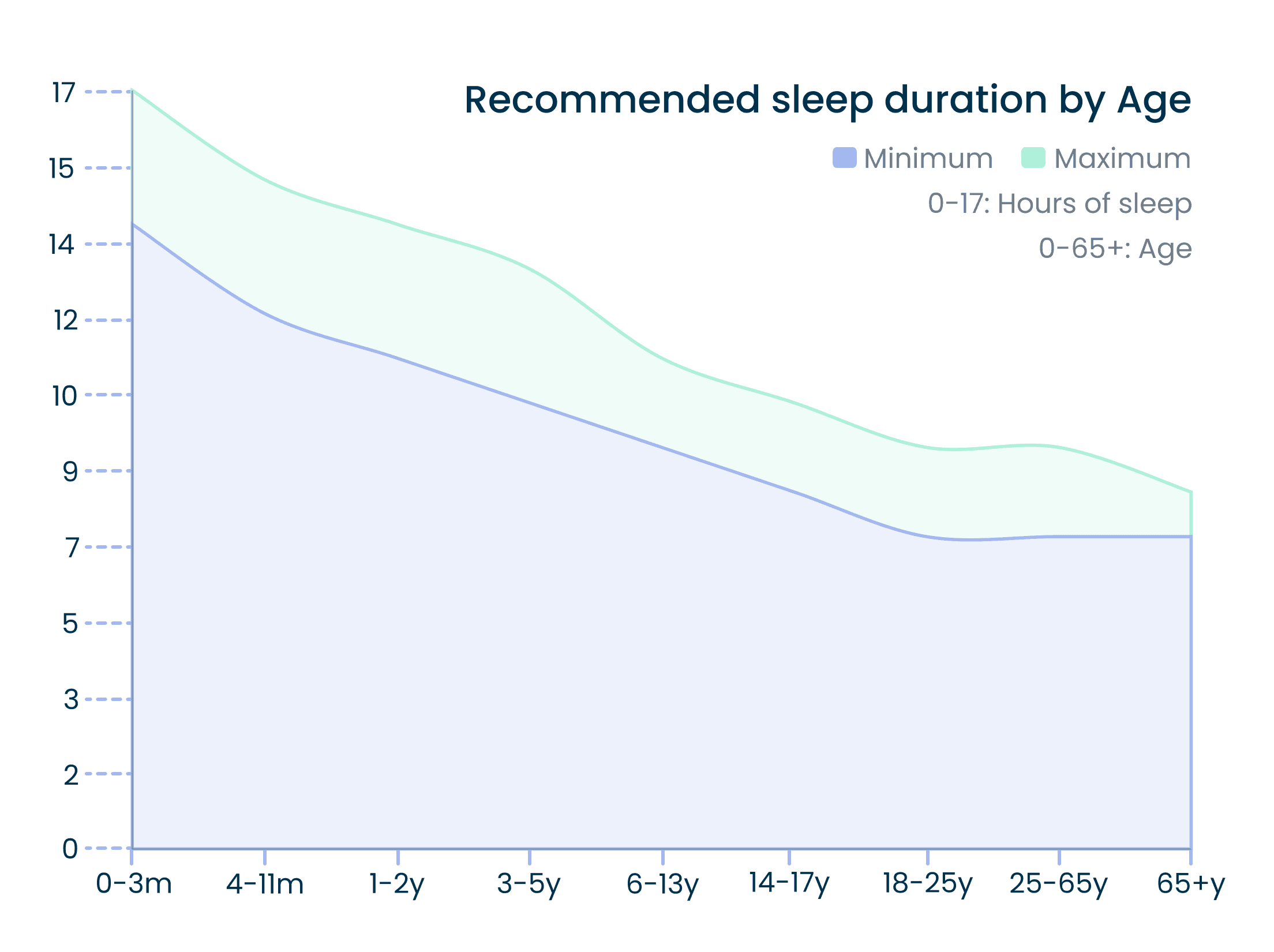

Sleep Requirements Throughout a Lifetime

The amount of sleep we need changes over the course of our lives. However, individual sleep needs may vary due to genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Below are the sleep duration recommendations from the National Sleep Foundation:¹

Newborns (0–3 months): 14–17 hours

Infants (4–11 months): 12–15 hours

Toddlers (1–2 years): 11–14 hours

Preschoolers (3–5 years): 10–13 hours

School-age children (6–13 years): 9–11 hours

Teenagers (14–17 years): 8–10 hours

Young adults (18–25 years): 7–9 hours

Adults (26–64 years): 7–9 hours

Older adults (65+ years): 7–8 hours

Besides the quantity of sleep, quality and timing play critical roles. Going to bed and waking up at consistent times aligns with the body’s circadian rhythm and ensures better performance and energy levels. Ultimately, good sleep should leave you feeling refreshed and able to function well throughout the day.

Health Impacts of Sleep Disruption

Sleep disruption, whether caused by insomnia, sleep apnea, or poor habits, has serious physical, cognitive, and emotional consequences.²

Short-Term Consequences of Sleep Disruption :

In Healthy Individuals:

Increased Stress Response:

Activates the sympathetic nervous system, increasing heart rate and blood pressure.

Heightened stress hormones affect mood and cognitive function.

Cognitive, Memory, and Performance Deficits:

Reduced attention, impaired decision-making, and emotional instability.

Mood Disorders and Emotional Distress:

Sleep loss contributes to anxiety, depression, and irritability.

Physical Symptoms:

Associated with headaches, abdominal pain, and general somatic discomfort.

In Adolescents:

Poor sleep linked to:

Decline in Academic Performance and increased risk-taking (e.g., substance use, reckless driving).

Mood disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety).

In Children:

Fragmented sleep associated with:

Behavioral issues, emotional dysregulation, and impaired cognitive functioning.

Higher incidence of self-harm and psychiatric symptoms.

In Individuals with Medical Conditions:

Sleep disruption exacerbates chronic illness symptoms, reducing the quality of life.

For example, dialysis patients and pediatric transplant recipients report diminished well-being due to disrupted sleep.

Long-Term Consequences of Sleep Disruption :

Cardiovascular Effects:

Increases risk of:

Hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Higher cholesterol and elevated body mass index (BMI) in adolescents.

Metabolic Disorders:

Contributes to:

Weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Hormonal imbalances affecting appetite (reduced leptin, increased ghrelin).

Cancer Risk:

Circadian Rhythm Disruption linked to:

Increased risk of colorectal and prostate cancer.

Reduced melatonin production disrupts tumor-suppressing activities.

Mortality:

Men with chronic sleep disturbances show a higher risk of all-cause mortality.

Sleep issues linked to suicide risk in adolescents.

Gastrointestinal Disorders:

Worsens symptoms of:

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Proactively managing sleep can prevent many of these long-term health risks and improve overall well-being.

Neuroprotective Aspects of Sleep

Sleep plays a critical role in maintaining brain health. During sleep, the brain undergoes processes essential for memory consolidation, emotional regulation, and waste clearance.³

Key Functions of Sleep:

Memory and Learning:

Sleep strengthens memory recall and forms new synaptic connections.

Different sleep stages, particularly NREM, play roles in consolidating long-term memory.

Brain Detoxification:

Sleep activates the glymphatic system, flushing out waste, including beta-amyloid, a substance linked to Alzheimer’s.

The system works efficiently only during sleep, using cerebrospinal fluid to clear toxins.

Neurochemical Regulation:

Sleep restores neurotransmitter sensitivity (e.g., norepinephrine, serotonin, histamine) by turning off their receptors temporarily.

Brain cells repair damage caused by free radicals during sleep.

Sleep Phases and Their Roles:

Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) Sleep:

Stages:

N1: Transition from wakefulness to sleep.

N2: Light sleep; body temperature drops, heart rate slows.

N3 (Delta Sleep): Deep sleep; essential for physical and mental restoration.

NREM reduces sympathetic nervous system activity, allowing rest and repair.

Rapid Eye Movement (REM) Sleep:

Linked with dreaming and emotional processing.

REM cycles occur 4–5 times per night and increase in duration towards morning.

Consequences of Sleep Deprivation on Brain Health:

Cognitive impairments, including poor concentration, memory loss, and slower reaction times.

Chronic sleep loss increases the risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Emotional instability, depression, and anxiety become more prevalent with insufficient sleep.

The Role of Melatonin in Regulating Sleep and Circadian Rhythm

Melatonin, often referred to as the “sleep hormone,” is essential for regulating the body’s internal clock. It is produced by the pineal gland in response to darkness, signaling the body that it’s time to sleep.⁴

Melatonin and Sleep:

Overview:

Melatonin is a key hormone that regulates sleep and circadian rhythms.

Disruptions in melatonin production or release can lead to sleep disorders, cognitive impairment, weakened immune responses, and increased risk for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

Key Functions and Regulation of Melatonin:

Melatonin Production:

Synthesized in the pineal gland from serotonin, primarily during darkness.

Promotes sleep by rising at night and falling with light exposure.

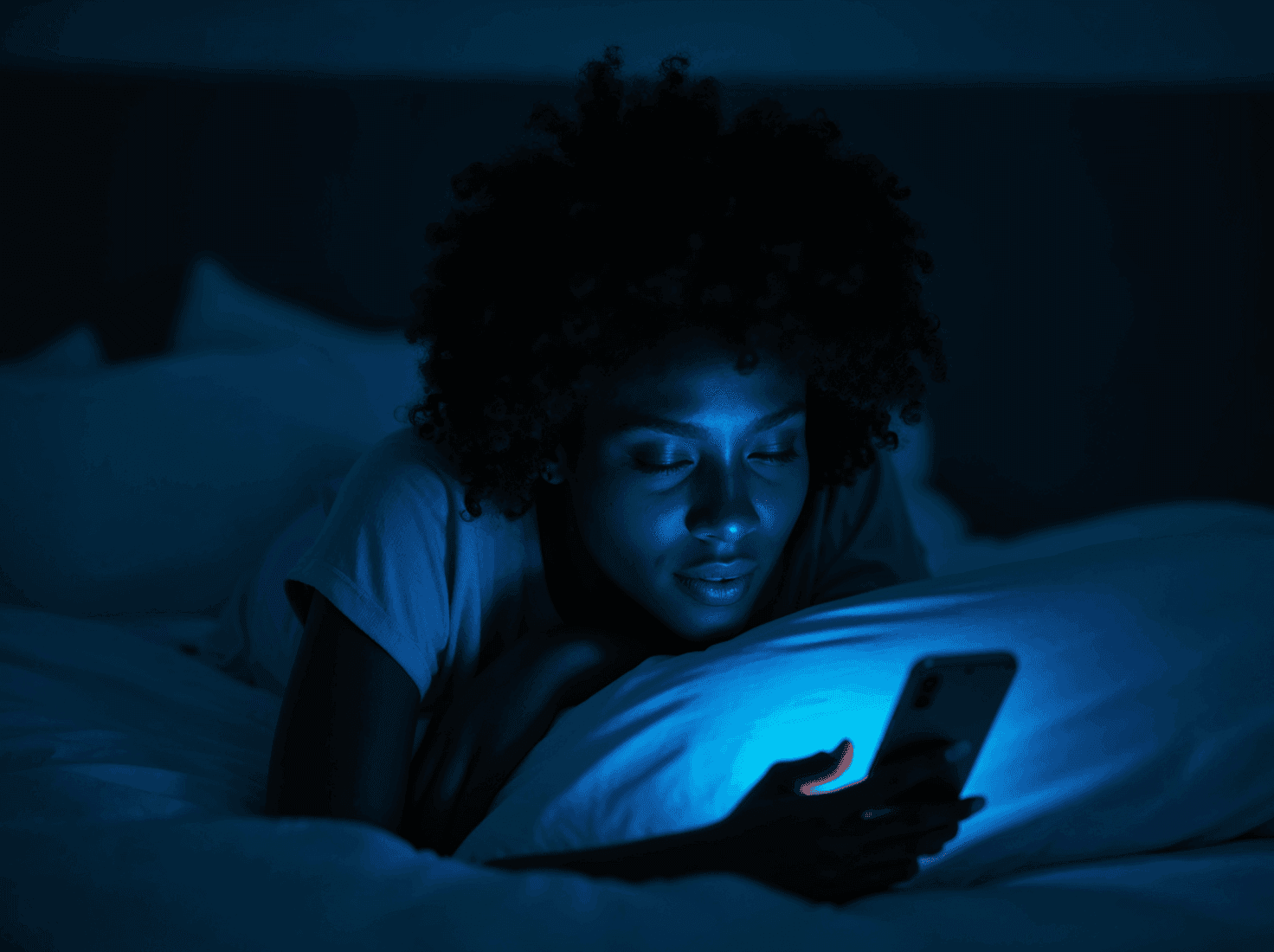

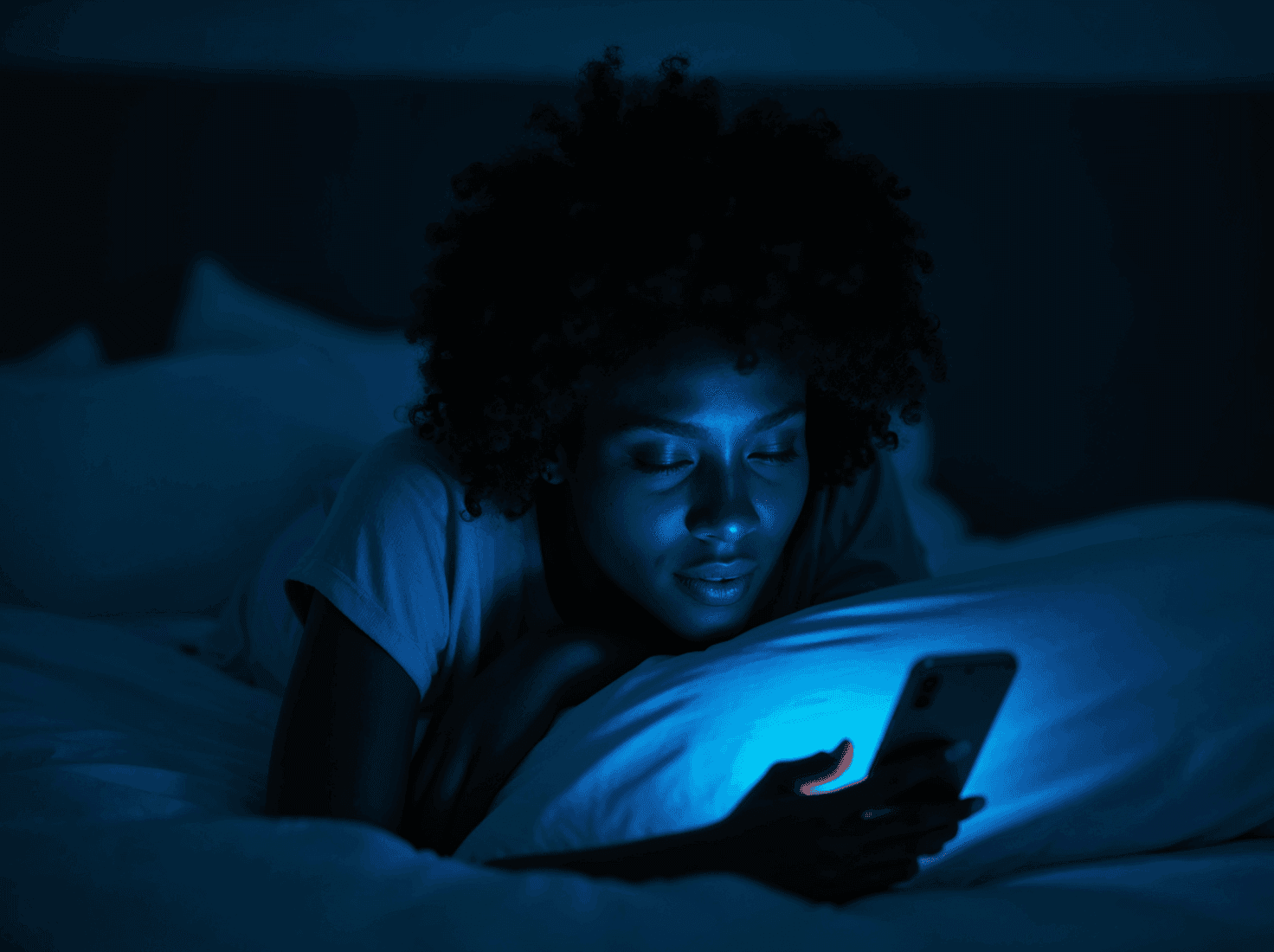

Suppressed by exposure to high-wavelength (blue) light, impacting sleep quality.

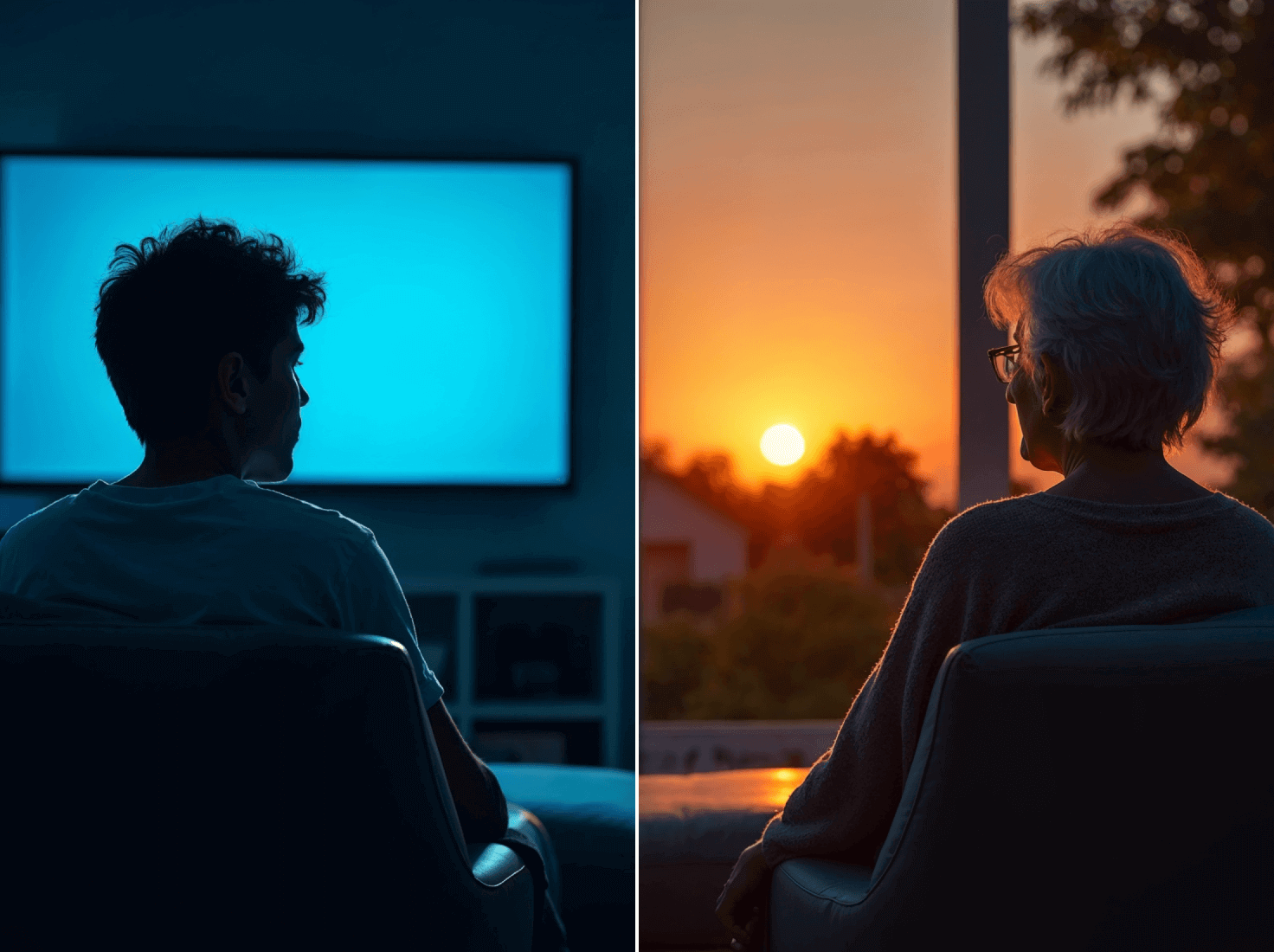

Circadian Rhythm Regulation:

Governed by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which signals the pineal gland based on light input from the retina.

Light exposure at abnormal times (e.g., night shifts) disrupts circadian rhythms, leading to melatonin suppression and health issues.

Disruptions in Circadian Rhythm and Melatonin Dysregulation:

Impact of Light Exposure:

Shift workers and individuals near the Earth’s poles are particularly vulnerable to melatonin disruption.

Electronic devices emitting blue light suppress melatonin, contributing to sleep disturbances.

Chronic light exposure at night (LAN) is linked to metabolic derangements and cancer risk.

Aging and Melatonin:

Melatonin production decreases with age, contributing to sleep fragmentation in older adults.

Age-related melatonin reduction may also be linked to pathological processes, such as Alzheimer's disease.

Therapeutic Interventions:

Bright Light Therapy (BLT):

Used to realign circadian rhythms and treat conditions like seasonal depression and fatigue.

Exposure to blue-enriched light during the day can improve sleep timing but excessive exposure to LAN disrupts melatonin synthesis.

Melatonin Supplementation:

Safe and non-habit forming, with minimal risk of toxicity.

Shown to improve circadian rhythms in cases such as jet lag, autism, and delayed sleep phase disorder.

Limitations: Melatonin’s efficacy is inconsistent, with more research needed to establish dosing and treatment protocols.

Potential Applications and Future Research:

Broader Use in Clinical Settings:

Melatonin may serve as a safer alternative to prescription sleep aids, especially for those tapering off benzodiazepines.

Further studies are required to explore melatonin’s role in managing metabolic disorders, psychiatric conditions, and neurological diseases.

Challenges in Research:

Variability in melatonin levels across individuals complicates dosing recommendations.

Limited studies on specific populations (e.g., elderly, racial differences) hinder comprehensive understanding.

Melatonin plays a critical role in maintaining healthy sleep patterns and regulating circadian rhythms. It's therapeutic potential is promising but underexplored, requiring further research to establish its efficacy across different health conditions. Managing light exposure and using melatonin supplements where appropriate can help restore circadian rhythms and improve overall well-being.

The Relationship Between Sleep, Social Media, Focus and Mental Health in Youth

The increasing use of social media among adolescents has complex effects on their mental health and sleep patterns.⁵

Key Findings

Increased Social Media Use (SMU) Linked to Poor Sleep and Mental Health:

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies reveal SMU contributes to sleep disturbances and mental health issues such as depression and anxiety in youth.

However, some studies found no direct link between SMU, sleep, and mental health, highlighting complex relationships.

Positive Role During COVID-19 Pandemic:

SMU provided social connection and emotional support, reducing stress during periods of restricted social interaction.

Adolescents used SMU to cope with exam pressure, seek support for mental health challenges, and offer help to peers.

SMU and Sleep

Delayed Sleep Onset and Shorter Sleep Duration:

Youth engaging in SMU near bedtime report later bedtimes and reduced sleep duration.

Adolescents with evening chronotype (night owls) tend to spend more time on social media, suggesting a bidirectional relationship between SMU and sleep patterns.

Blue Light Suppression of Melatonin:

Screen light exposure (especially blue light) at night disrupts melatonin release, impacting sleep quality and duration.

Adolescents sensitive to melatonin disruption (e.g., with mental health risk factors) are at greater risk of sleep problems.

Sleep as a Mediator:

Poor sleep caused by SMU also increases daytime sleepiness and worsens mental health outcomes.

SMU and Mental Health

Link to Depression, Anxiety, and Low Self-Esteem:

Greater time on social media correlates with higher risks of depression, self-harm, and lower self-esteem.

Mental health issues can also increase time spent on social media, showing a bidirectional link.

FOMO (Fear of Missing Out):

Youth experience peer pressure and compulsive SMU to stay connected, leading to emotional stress and sleep disturbances.

Cyberbullying and Mental Health:

SMU increases the risk of cyberbullying, further impacting youth's mental health, with effects ranging from depression to suicidal ideation.

Recommendations for Healthy SMU ⁶

Set Screen-Time Limits:

Limit SMU 1 hour before bedtime to reduce its impact on sleep.

Follow guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics and WHO on reducing screen time.

Promote Psychoeducation and Behavioral Interventions:

Schools and families should educate youth about managing SMU and practicing healthy habits like setting screen-time limits and using blue-light filters.

How Sleep Enhances Cognitive Performance and Focus

Sleep is essential for maintaining vigilant attention—the ability to stay focused and respond quickly over time. Sleep deprivation impairs cognitive abilities, leading to poor decision-making, slower reaction times, and more errors.

Key Insights on Vigilant Attention and Sleep

Vigilant Attention:

Refers to the ability to maintain focus and quickly respond to stimuli over time.

It is essential for tasks requiring continuous concentration, such as driving or studying.

Impact of Sleep on Focus and Vigilant Attention

Sleep Deprivation Weakens Focus:

Lack of sleep impairs vigilance, leading to slower reaction times and more errors in tasks.

Deficits build up across consecutive days of limited sleep, making recovery more challenging.

Rest Restores Vigilant Attention:

Sleep restores focus and reduces variability in task performance, helping maintain consistent attention.

Recovery from acute sleep deprivation is faster than recovery from long-term sleep restriction.

Factors Affecting Vigilant Attention Deficits

Circadian and Homeostatic Processes:

Your circadian rhythm (internal clock) regulates alertness during the day and drowsiness at night.

Homeostatic pressure builds during the day and signals the need for sleep by night.

Morning vs. Evening Performance:

Sleep deprivation affects focus most in the morning, but afternoon alertness often improves temporarily due to the circadian wake drive.

Inter-Individual Differences:

People vary in their vulnerability to sleep deprivation; some experience greater lapses in attention than others, even with the same sleep loss.

How Sleep Deprivation Impacts Performance

Time-on-Task Effect:

Performance declines as time on a task increases, especially under sleep deprivation, due to cognitive fatigue.

Short breaks help reset focus, but only sleep can fully restore cognitive abilities.

Response Variability:

Sleep-deprived individuals show more inconsistent responses, with slower reactions interspersed among normal ones.

Local Sleep Theory:

Even while awake, small brain regions may enter a sleep-like state, impairing information processing and causing lapses in attention.

Practical Tips for Maintaining Focus Through Sleep

Prioritize Regular Sleep:

Aim for 7-9 hours of sleep each night to maintain focus and cognitive performance.

Avoid chronic sleep restriction, which leads to cumulative focus deficits.

Take Short Breaks:

Use brief rest breaks or task-switching to reset focus during long periods of work.

Optimize Morning Alertness:

Utilize bright morning light exposure to enhance the circadian wake drive.

Minimize Sleep Disruptions:

Create a consistent sleep schedule to improve overall focus and performance.

Understanding the relationship between sleep and focus underscores the importance of healthy sleep habits. Integrating regular sleep into your routine will help sustain attention and enhance cognitive performance, especially during critical tasks.

Comprehensive Toolkit for Better Sleep and Circadian Health

This toolkit offers practical steps to optimize your sleep and align your circadian rhythm:

Morning Routine:

Get Sunlight: Spend 10–30 minutes in natural light within an hour of waking.

Delay Caffeine: Wait 90 minutes after waking to drink coffee to avoid energy crashes later.

Incorporate Movement: Light exercise in the morning boosts alertness and energy.

Limit Phone Use: Avoid screens for the first 30 minutes after waking.

Daytime Actions:

Practice NSDR (Non-Sleep Deep Rest): Techniques like Yoga Nidra calm the nervous system and improve sleep quality.

Stop Caffeine by 3 PM: Avoid caffeine after this time to prevent sleep disruption.

Optional Naps: Keep naps under 90 minutes and take them before 4 PM.

Watch the Sunset: Exposing your eyes to sunset light signals your body to prepare for sleep.

Evening Routine:

Create a Wind-Down Routine: Dim lights, stretch, or read to signal bedtime.

Optimize Your Sleep Environment: Keep your room cool and dark for optimal rest.

Avoid Late Meals: Finish eating 3–4 hours before bedtime.

Reduce Light Exposure: Use low-level lights and activate night mode on devices.

Use Mouth Tape (Optional):

Mouth taping encourages nasal breathing, reducing snoring and improving sleep quality.

Sleep on Your Side: Side-sleeping supports better breathing and reduces muscle strain.

Optimal Sleep Supplements (Optional):

Taking the right supplements before bed can enhance relaxation and support better sleep:

Magnesium Threonate or Bisglycinate: 145 mg or 200 mg, to promote relaxation.

Apigenin: 50 mg, for its calming effects.

Theanine: 100–400 mg, to improve sleep without sedation (avoid if prone to vivid dreams).

Glycine (2g) and GABA (100 mg): Recommended 3–4 nights a week for nervous system relaxation.

Note: Always consult with a healthcare provider before starting any new supplements, especially if you have existing health conditions.

Lifestyle Tips for Circadian Rhythm and Jet Lag Management:

Exercise in the Morning: Morning workouts align with your circadian rhythm and promote restful sleep.

Gradually Shift Sleep Schedules: If adjusting your bedtime or wake-up time, shift it by 15-minute increments until you reach your goal.

Prepare for Jet Lag: Eat and sleep according to your destination’s schedule a few days before traveling. Use light exposure to shift your internal clock—eastward travel requires earlier exposure, while westward travel requires later exposure.

Avoid Alcohol and Sleep Medications: While alcohol or sleep meds may help you fall asleep faster, they disrupt sleep quality and the natural sleep cycle.

Consistency Over Duration: Stick to the same bedtime and wake-up time every day—even on weekends. Sleep consistency has a greater impact on health than sleeping in on weekends.

Regular Exercise at the Same Time Each Day: This helps regulate neurotransmitter activity, improving both sleep quality and circadian rhythm alignment.

Source : https://www.hubermanlab.com/newsletter/toolkit-for-sleep and the Huberman Lab Podcast series on Sleep.

Conclusion: Make Sleep a Priority for a Healthier Life

Good sleep is more than just a luxury—it’s essential for long-term health, cognitive performance, emotional balance, and overall well-being. By understanding the science behind sleep and incorporating small but effective changes into your daily routine, you can significantly enhance your quality of life.

Key Takeaways for Better Sleep:

Align your schedule with your natural circadian rhythm.

Minimize exposure to blue light in the evening and increase morning sunlight exposure.

Develop a consistent bedtime routine to signal your body that it’s time to sleep.

Avoid caffeine, alcohol, and heavy meals in the hours leading up to bedtime.

Consider non-invasive supplements or therapies if needed, but always consult with a healthcare provider.

Final Thought:

By making small changes—such as following a consistent sleep schedule, limiting evening screen time, and optimizing your sleep environment—you’ll be able to experience the profound benefits of restorative sleep. Better sleep leads to better health, sharper focus, and a more fulfilling life.

Sources :

Chaput, J., Dutil, C., & Sampasa-Kanyinga, H. (2018). Sleeping hours: what is the ideal number and how does age impact this? Nature and Science of Sleep, Volume 10, 421–430. https://doi.org/10.2147/nss.s163071

Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep, Volume 9, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.2147/nss.s134864

Eugene, A. R., & Masiak, J. (2015, March 1). The neuroprotective aspects of sleep. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4651462/

Vasey, C., McBride, J., & Penta, K. (2021). Circadian rhythm Dysregulation and restoration: the role of melatonin. Nutrients, 13(10), 3480. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103480

Hudson, A. N., Van Dongen, H. P. A., & Honn, K. A. (2019). Sleep deprivation, vigilant attention, and brain function: a review. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0432-6

Yu, D. J., Wing, Y. K., Li, T. M. H., & Chan, N. Y. (2024). The Impact of Social Media Use on Sleep and Mental Health in Youth: a Scoping Review. Current Psychiatry Reports. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-024-01481-9

Current version

Oct 15, 2024

Written by

Eileen Quinones (Certified Family Nurse Practitioner)

Lose weight effectively

with GLP-1s

Fill out a quick form to share your

medical history, helping us tailor the

perfect plan for you.

Similar Health Guides

Lose weight effectively

with GLP-1s

Fill out a quick form to share your

medical history, helping us tailor the

perfect plan for you.

Lose weight effectively

with GLP-1s

Fill out a quick form to share your

medical history, helping us tailor the

perfect plan for you.

Get meds delivered from

the comfort of your home.

Download our app now, and get amazing rewards!

The Importance of Sleep: Enhancing Health, Mind, and Performance

Lifestyle

Eileen Quinones

•

15 mins read

• Oct 15, 2024

Sleep is a cornerstone of human health, as essential as exercise and nutrition. It supports physical recovery, cognitive function, and emotional well-being. Despite this, many people underestimate its importance, leading to widespread sleep disruption that negatively impacts performance and health. This blog dives deep into the science of sleep, the health risks associated with poor sleep, and practical strategies to cultivate healthy sleep habits.

Sleep Requirements Throughout a Lifetime

The amount of sleep we need changes over the course of our lives. However, individual sleep needs may vary due to genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Below are the sleep duration recommendations from the National Sleep Foundation:¹

Newborns (0–3 months): 14–17 hours

Infants (4–11 months): 12–15 hours

Toddlers (1–2 years): 11–14 hours

Preschoolers (3–5 years): 10–13 hours

School-age children (6–13 years): 9–11 hours

Teenagers (14–17 years): 8–10 hours

Young adults (18–25 years): 7–9 hours

Adults (26–64 years): 7–9 hours

Older adults (65+ years): 7–8 hours

Besides the quantity of sleep, quality and timing play critical roles. Going to bed and waking up at consistent times aligns with the body’s circadian rhythm and ensures better performance and energy levels. Ultimately, good sleep should leave you feeling refreshed and able to function well throughout the day.

Health Impacts of Sleep Disruption

Sleep disruption, whether caused by insomnia, sleep apnea, or poor habits, has serious physical, cognitive, and emotional consequences.²

Short-Term Consequences of Sleep Disruption :

In Healthy Individuals:

Increased Stress Response:

Activates the sympathetic nervous system, increasing heart rate and blood pressure.

Heightened stress hormones affect mood and cognitive function.

Cognitive, Memory, and Performance Deficits:

Reduced attention, impaired decision-making, and emotional instability.

Mood Disorders and Emotional Distress:

Sleep loss contributes to anxiety, depression, and irritability.

Physical Symptoms:

Associated with headaches, abdominal pain, and general somatic discomfort.

In Adolescents:

Poor sleep linked to:

Decline in Academic Performance and increased risk-taking (e.g., substance use, reckless driving).

Mood disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety).

In Children:

Fragmented sleep associated with:

Behavioral issues, emotional dysregulation, and impaired cognitive functioning.

Higher incidence of self-harm and psychiatric symptoms.

In Individuals with Medical Conditions:

Sleep disruption exacerbates chronic illness symptoms, reducing the quality of life.

For example, dialysis patients and pediatric transplant recipients report diminished well-being due to disrupted sleep.

Long-Term Consequences of Sleep Disruption :

Cardiovascular Effects:

Increases risk of:

Hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Higher cholesterol and elevated body mass index (BMI) in adolescents.

Metabolic Disorders:

Contributes to:

Weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Hormonal imbalances affecting appetite (reduced leptin, increased ghrelin).

Cancer Risk:

Circadian Rhythm Disruption linked to:

Increased risk of colorectal and prostate cancer.

Reduced melatonin production disrupts tumor-suppressing activities.

Mortality:

Men with chronic sleep disturbances show a higher risk of all-cause mortality.

Sleep issues linked to suicide risk in adolescents.

Gastrointestinal Disorders:

Worsens symptoms of:

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Proactively managing sleep can prevent many of these long-term health risks and improve overall well-being.

Neuroprotective Aspects of Sleep

Sleep plays a critical role in maintaining brain health. During sleep, the brain undergoes processes essential for memory consolidation, emotional regulation, and waste clearance.³

Key Functions of Sleep:

Memory and Learning:

Sleep strengthens memory recall and forms new synaptic connections.

Different sleep stages, particularly NREM, play roles in consolidating long-term memory.

Brain Detoxification:

Sleep activates the glymphatic system, flushing out waste, including beta-amyloid, a substance linked to Alzheimer’s.

The system works efficiently only during sleep, using cerebrospinal fluid to clear toxins.

Neurochemical Regulation:

Sleep restores neurotransmitter sensitivity (e.g., norepinephrine, serotonin, histamine) by turning off their receptors temporarily.

Brain cells repair damage caused by free radicals during sleep.

Sleep Phases and Their Roles:

Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) Sleep:

Stages:

N1: Transition from wakefulness to sleep.

N2: Light sleep; body temperature drops, heart rate slows.

N3 (Delta Sleep): Deep sleep; essential for physical and mental restoration.

NREM reduces sympathetic nervous system activity, allowing rest and repair.

Rapid Eye Movement (REM) Sleep:

Linked with dreaming and emotional processing.

REM cycles occur 4–5 times per night and increase in duration towards morning.

Consequences of Sleep Deprivation on Brain Health:

Cognitive impairments, including poor concentration, memory loss, and slower reaction times.

Chronic sleep loss increases the risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Emotional instability, depression, and anxiety become more prevalent with insufficient sleep.

The Role of Melatonin in Regulating Sleep and Circadian Rhythm

Melatonin, often referred to as the “sleep hormone,” is essential for regulating the body’s internal clock. It is produced by the pineal gland in response to darkness, signaling the body that it’s time to sleep.⁴

Melatonin and Sleep:

Overview:

Melatonin is a key hormone that regulates sleep and circadian rhythms.

Disruptions in melatonin production or release can lead to sleep disorders, cognitive impairment, weakened immune responses, and increased risk for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

Key Functions and Regulation of Melatonin:

Melatonin Production:

Synthesized in the pineal gland from serotonin, primarily during darkness.

Promotes sleep by rising at night and falling with light exposure.

Suppressed by exposure to high-wavelength (blue) light, impacting sleep quality.

Circadian Rhythm Regulation:

Governed by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which signals the pineal gland based on light input from the retina.

Light exposure at abnormal times (e.g., night shifts) disrupts circadian rhythms, leading to melatonin suppression and health issues.

Disruptions in Circadian Rhythm and Melatonin Dysregulation:

Impact of Light Exposure:

Shift workers and individuals near the Earth’s poles are particularly vulnerable to melatonin disruption.

Electronic devices emitting blue light suppress melatonin, contributing to sleep disturbances.

Chronic light exposure at night (LAN) is linked to metabolic derangements and cancer risk.

Aging and Melatonin:

Melatonin production decreases with age, contributing to sleep fragmentation in older adults.

Age-related melatonin reduction may also be linked to pathological processes, such as Alzheimer's disease.

Therapeutic Interventions:

Bright Light Therapy (BLT):

Used to realign circadian rhythms and treat conditions like seasonal depression and fatigue.

Exposure to blue-enriched light during the day can improve sleep timing but excessive exposure to LAN disrupts melatonin synthesis.

Melatonin Supplementation:

Safe and non-habit forming, with minimal risk of toxicity.

Shown to improve circadian rhythms in cases such as jet lag, autism, and delayed sleep phase disorder.

Limitations: Melatonin’s efficacy is inconsistent, with more research needed to establish dosing and treatment protocols.

Potential Applications and Future Research:

Broader Use in Clinical Settings:

Melatonin may serve as a safer alternative to prescription sleep aids, especially for those tapering off benzodiazepines.

Further studies are required to explore melatonin’s role in managing metabolic disorders, psychiatric conditions, and neurological diseases.

Challenges in Research:

Variability in melatonin levels across individuals complicates dosing recommendations.

Limited studies on specific populations (e.g., elderly, racial differences) hinder comprehensive understanding.

Melatonin plays a critical role in maintaining healthy sleep patterns and regulating circadian rhythms. It's therapeutic potential is promising but underexplored, requiring further research to establish its efficacy across different health conditions. Managing light exposure and using melatonin supplements where appropriate can help restore circadian rhythms and improve overall well-being.

The Relationship Between Sleep, Social Media, Focus and Mental Health in Youth

The increasing use of social media among adolescents has complex effects on their mental health and sleep patterns.⁵

Key Findings

Increased Social Media Use (SMU) Linked to Poor Sleep and Mental Health:

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies reveal SMU contributes to sleep disturbances and mental health issues such as depression and anxiety in youth.

However, some studies found no direct link between SMU, sleep, and mental health, highlighting complex relationships.

Positive Role During COVID-19 Pandemic:

SMU provided social connection and emotional support, reducing stress during periods of restricted social interaction.

Adolescents used SMU to cope with exam pressure, seek support for mental health challenges, and offer help to peers.

SMU and Sleep

Delayed Sleep Onset and Shorter Sleep Duration:

Youth engaging in SMU near bedtime report later bedtimes and reduced sleep duration.

Adolescents with evening chronotype (night owls) tend to spend more time on social media, suggesting a bidirectional relationship between SMU and sleep patterns.

Blue Light Suppression of Melatonin:

Screen light exposure (especially blue light) at night disrupts melatonin release, impacting sleep quality and duration.

Adolescents sensitive to melatonin disruption (e.g., with mental health risk factors) are at greater risk of sleep problems.

Sleep as a Mediator:

Poor sleep caused by SMU also increases daytime sleepiness and worsens mental health outcomes.

SMU and Mental Health

Link to Depression, Anxiety, and Low Self-Esteem:

Greater time on social media correlates with higher risks of depression, self-harm, and lower self-esteem.

Mental health issues can also increase time spent on social media, showing a bidirectional link.

FOMO (Fear of Missing Out):

Youth experience peer pressure and compulsive SMU to stay connected, leading to emotional stress and sleep disturbances.

Cyberbullying and Mental Health:

SMU increases the risk of cyberbullying, further impacting youth's mental health, with effects ranging from depression to suicidal ideation.

Recommendations for Healthy SMU ⁶

Set Screen-Time Limits:

Limit SMU 1 hour before bedtime to reduce its impact on sleep.

Follow guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics and WHO on reducing screen time.

Promote Psychoeducation and Behavioral Interventions:

Schools and families should educate youth about managing SMU and practicing healthy habits like setting screen-time limits and using blue-light filters.

How Sleep Enhances Cognitive Performance and Focus

Sleep is essential for maintaining vigilant attention—the ability to stay focused and respond quickly over time. Sleep deprivation impairs cognitive abilities, leading to poor decision-making, slower reaction times, and more errors.

Key Insights on Vigilant Attention and Sleep

Vigilant Attention:

Refers to the ability to maintain focus and quickly respond to stimuli over time.

It is essential for tasks requiring continuous concentration, such as driving or studying.

Impact of Sleep on Focus and Vigilant Attention

Sleep Deprivation Weakens Focus:

Lack of sleep impairs vigilance, leading to slower reaction times and more errors in tasks.

Deficits build up across consecutive days of limited sleep, making recovery more challenging.

Rest Restores Vigilant Attention:

Sleep restores focus and reduces variability in task performance, helping maintain consistent attention.

Recovery from acute sleep deprivation is faster than recovery from long-term sleep restriction.

Factors Affecting Vigilant Attention Deficits

Circadian and Homeostatic Processes:

Your circadian rhythm (internal clock) regulates alertness during the day and drowsiness at night.

Homeostatic pressure builds during the day and signals the need for sleep by night.

Morning vs. Evening Performance:

Sleep deprivation affects focus most in the morning, but afternoon alertness often improves temporarily due to the circadian wake drive.

Inter-Individual Differences:

People vary in their vulnerability to sleep deprivation; some experience greater lapses in attention than others, even with the same sleep loss.

How Sleep Deprivation Impacts Performance

Time-on-Task Effect:

Performance declines as time on a task increases, especially under sleep deprivation, due to cognitive fatigue.

Short breaks help reset focus, but only sleep can fully restore cognitive abilities.

Response Variability:

Sleep-deprived individuals show more inconsistent responses, with slower reactions interspersed among normal ones.

Local Sleep Theory:

Even while awake, small brain regions may enter a sleep-like state, impairing information processing and causing lapses in attention.

Practical Tips for Maintaining Focus Through Sleep

Prioritize Regular Sleep:

Aim for 7-9 hours of sleep each night to maintain focus and cognitive performance.

Avoid chronic sleep restriction, which leads to cumulative focus deficits.

Take Short Breaks:

Use brief rest breaks or task-switching to reset focus during long periods of work.

Optimize Morning Alertness:

Utilize bright morning light exposure to enhance the circadian wake drive.

Minimize Sleep Disruptions:

Create a consistent sleep schedule to improve overall focus and performance.

Understanding the relationship between sleep and focus underscores the importance of healthy sleep habits. Integrating regular sleep into your routine will help sustain attention and enhance cognitive performance, especially during critical tasks.

Comprehensive Toolkit for Better Sleep and Circadian Health

This toolkit offers practical steps to optimize your sleep and align your circadian rhythm:

Morning Routine:

Get Sunlight: Spend 10–30 minutes in natural light within an hour of waking.

Delay Caffeine: Wait 90 minutes after waking to drink coffee to avoid energy crashes later.

Incorporate Movement: Light exercise in the morning boosts alertness and energy.

Limit Phone Use: Avoid screens for the first 30 minutes after waking.

Daytime Actions:

Practice NSDR (Non-Sleep Deep Rest): Techniques like Yoga Nidra calm the nervous system and improve sleep quality.

Stop Caffeine by 3 PM: Avoid caffeine after this time to prevent sleep disruption.

Optional Naps: Keep naps under 90 minutes and take them before 4 PM.

Watch the Sunset: Exposing your eyes to sunset light signals your body to prepare for sleep.

Evening Routine:

Create a Wind-Down Routine: Dim lights, stretch, or read to signal bedtime.

Optimize Your Sleep Environment: Keep your room cool and dark for optimal rest.

Avoid Late Meals: Finish eating 3–4 hours before bedtime.

Reduce Light Exposure: Use low-level lights and activate night mode on devices.

Use Mouth Tape (Optional):

Mouth taping encourages nasal breathing, reducing snoring and improving sleep quality.

Sleep on Your Side: Side-sleeping supports better breathing and reduces muscle strain.

Optimal Sleep Supplements (Optional):

Taking the right supplements before bed can enhance relaxation and support better sleep:

Magnesium Threonate or Bisglycinate: 145 mg or 200 mg, to promote relaxation.

Apigenin: 50 mg, for its calming effects.

Theanine: 100–400 mg, to improve sleep without sedation (avoid if prone to vivid dreams).

Glycine (2g) and GABA (100 mg): Recommended 3–4 nights a week for nervous system relaxation.

Note: Always consult with a healthcare provider before starting any new supplements, especially if you have existing health conditions.

Lifestyle Tips for Circadian Rhythm and Jet Lag Management:

Exercise in the Morning: Morning workouts align with your circadian rhythm and promote restful sleep.

Gradually Shift Sleep Schedules: If adjusting your bedtime or wake-up time, shift it by 15-minute increments until you reach your goal.

Prepare for Jet Lag: Eat and sleep according to your destination’s schedule a few days before traveling. Use light exposure to shift your internal clock—eastward travel requires earlier exposure, while westward travel requires later exposure.

Avoid Alcohol and Sleep Medications: While alcohol or sleep meds may help you fall asleep faster, they disrupt sleep quality and the natural sleep cycle.

Consistency Over Duration: Stick to the same bedtime and wake-up time every day—even on weekends. Sleep consistency has a greater impact on health than sleeping in on weekends.

Regular Exercise at the Same Time Each Day: This helps regulate neurotransmitter activity, improving both sleep quality and circadian rhythm alignment.

Source : https://www.hubermanlab.com/newsletter/toolkit-for-sleep and the Huberman Lab Podcast series on Sleep.

Conclusion: Make Sleep a Priority for a Healthier Life

Good sleep is more than just a luxury—it’s essential for long-term health, cognitive performance, emotional balance, and overall well-being. By understanding the science behind sleep and incorporating small but effective changes into your daily routine, you can significantly enhance your quality of life.

Key Takeaways for Better Sleep:

Align your schedule with your natural circadian rhythm.

Minimize exposure to blue light in the evening and increase morning sunlight exposure.

Develop a consistent bedtime routine to signal your body that it’s time to sleep.

Avoid caffeine, alcohol, and heavy meals in the hours leading up to bedtime.

Consider non-invasive supplements or therapies if needed, but always consult with a healthcare provider.

Final Thought:

By making small changes—such as following a consistent sleep schedule, limiting evening screen time, and optimizing your sleep environment—you’ll be able to experience the profound benefits of restorative sleep. Better sleep leads to better health, sharper focus, and a more fulfilling life.

Current version

Oct 15, 2024

Written by

Eileen Quinones (Certified Family Nurse Practitioner)

Fact checked by

Dr. Jonathan Hinds (MD, FACEP, Certified Physician)

Sources :

Chaput, J., Dutil, C., & Sampasa-Kanyinga, H. (2018). Sleeping hours: what is the ideal number and how does age impact this? Nature and Science of Sleep, Volume 10, 421–430. https://doi.org/10.2147/nss.s163071

Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep, Volume 9, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.2147/nss.s134864

Eugene, A. R., & Masiak, J. (2015, March 1). The neuroprotective aspects of sleep. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4651462/

Vasey, C., McBride, J., & Penta, K. (2021). Circadian rhythm Dysregulation and restoration: the role of melatonin. Nutrients, 13(10), 3480. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103480

Hudson, A. N., Van Dongen, H. P. A., & Honn, K. A. (2019). Sleep deprivation, vigilant attention, and brain function: a review. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0432-6

Yu, D. J., Wing, Y. K., Li, T. M. H., & Chan, N. Y. (2024). The Impact of Social Media Use on Sleep and Mental Health in Youth: a Scoping Review. Current Psychiatry Reports. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-024-01481-9